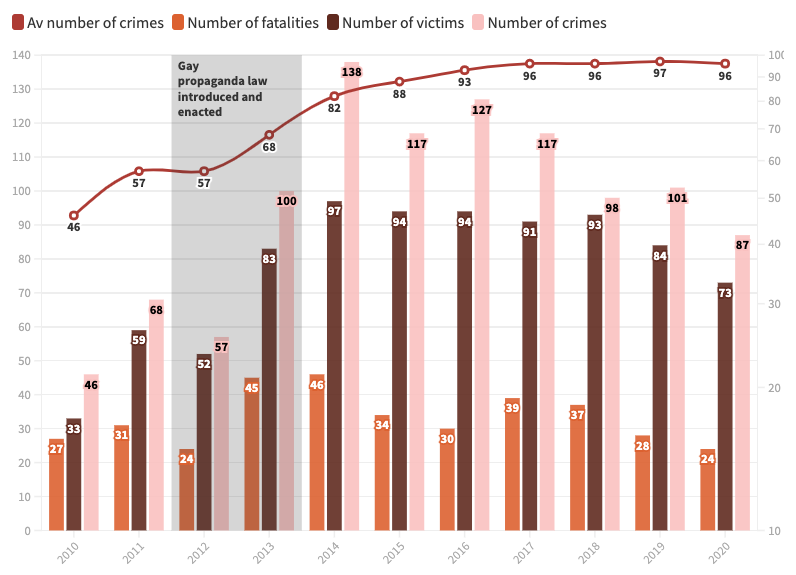

The number of hate crimes against LGBTQ people in Russia has been growing every year for at least a decade. This has been facilitated, above all, by the existence of discriminatory legislation—including the so-called “gay propaganda law.” Our research group based at University College Dublin developed a method for identifying anti-LGBTQ hate crimes in open databases of court rulings in Russia. Utilizing this method, we were able to gather a database of such crimes. Our data show that homophobic violence has been on the rise in Russia since the introduction of the “gay propaganda” law. We find that between 2010 and 2020, 1,056 hate crimes were committed against 853 individuals, with 365 fatalities. Overall, the number of crimes perpetrated on an annual basis since the enactment of the “gay propaganda” law has been three times higher than prior to the law. In addition to this quantitative change, crimes against LGBTQ people have changed qualitatively: since the 2013 law, not only have they have become more violent, but there are also more crimes that are premeditated and committed by a group of perpetrators. Both the quantitative and qualitative changes in the level of anti-LGBTQ hate crime in Russia are attributable to the introduction of the “gay propaganda law.”

The hate crimes listed in our database, however numerous, are still a drop in the ocean of homophobic violence committed in Russia. In our analysis, we include only those crimes that reached the court—which, according to the Russian LGBT Network, a prominent LGBT rights NGO in Russia, usually account for just 2 to 7 percent of the total number of hate crimes. Most of the cases identified by our research team were neither covered by the media nor overlooked by NGOs. The Russian authorities do not monitor such crimes, instead making such statements as “We don’t have these kinds of people here, we don’t have any gays. You cannot kill those who don’t exist” (Kadyrov, 2017). The purpose of the research was to refute this claim. To do so, we searched all the criminal cases available to the public and applied definitions of “hate crime” to identify anti-LGBTQ hate crimes among these cases.

Definitions of “Hate Crime” and “Bias Motive”

What is a hate crime? According to the definition given by the OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR), hate crimes include criminal offenses committed with a bias motive and motivated by prejudice against a particular social group (based on race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, etc.). Such crimes are usually directed not at a specific individual but at the group as a whole, and the victims are generally interchangeable.

The key concept here is the bias motive, which can manifest itself in different ways. In the first variant, the perpetrators choose the victim because of their own hostile feelings toward the social group to which the victim belongs. Often, the perpetrators somehow express this hatred: for example, the notorious Maxim Martsinkevich (aka “Tesak”), whose followers carried out serial attacks on LGBTQ people in Russia, openly declared that the motive for his actions was the rejection of homosexuality. In his book Restrukt, Tesak wrote that he “relies on the laws of nature, and therefore does not allow any tolerance for homosexuals, [he] hates them, like all other vices.” In all subsequent crimes committed by Tesak and his followers, this open hatred could be observed. The ODIHR terms this the “hostility model” of hate crime; it implies a well-documented negative attitude toward the targeted group on the part of the offender. In the vast majority of cases, this motive is indicated by the actions or words of the criminals themselves. For example, an excerpt from the court judgment may testify to this, as with Case 1-11/2021 from the city of Vorkuta: “In the summer of 2014, the perpetrator met Rudenko, who asked for help. He said that there is a gay man in the neighborhood, and that he wants to punish him.”

In the second variant, the criminals are indifferent to the social group to which the victim belongs but commit the crime because the victim is a “convenient target” for them. For example, many of those who commit robberies and assaults against LGBTQ people in Russia are guided primarily by pragmatism: their victims are unlikely to go to the police, as doing so would require them to reveal their own sexual orientation. Yet despite the absence of open hatred, this is still a hate crime, as the key element of the act is the motive of prejudice against a certain social group. The ODIHR terms this the “discriminatory selection model,” in which the victim is chosen “because of” or “due to” their presumed group membership, while the element of enmity or hatred on the part of the perpetrator may be absent. Consider the following example from Case 2-7/2014 from the Moscow City Court, in which the defendant described selecting victims in a discriminatory way:

Defendant M pleaded guilty at the hearing and testified that he met K in 2010. < … > M had financial difficulties, which K knew about, and the latter suggested robbing people of non-traditional sexual orientation, finding them on the Internet, to which M agreed.

Effects of Discrimination on the Level of Hate Crime

What can increase the level of hate crime in society? One factor is the presence of discriminatory legislation. Such laws restrict the rights of a salient social group and introduce inequality. This state of affairs becomes dangerous—social scientists agree that discriminatory laws increase the level of violence against the discriminated group.

In 2023, there was a dark anniversary of the “gay propaganda law”—10 years from the moment when it entered into force. It was introduced in June-July 2013 and included amendments to the Code of Administrative Offenses that imposed liability for “propaganda of non-traditional sexual relations among minors.” The definition of such “promotion” is very vague, leaving broad discretion to the police and judges. The only pattern that can be observed in the case law is that any positive or neutral LGBTQ-related expressions are restricted. This represents a blanket ban: as the Russian Constitutional Court puts it, when dealing with expressions related to sexuality, there is a “presumption of danger,” which means the expressions are a priori dangerous unless proven otherwise, which allows law enforcement to restrict anything LGBTQ-related—cases of “gay propaganda” range from wearing rainbow prints to screening LGBTQ movies. The “gay propaganda” article was used relatively infrequently: in 10 years, just over 50 persons and organizations were found guilty of “gay propaganda.” Despite such ineffective law enforcement, the law performed a different function. It increased negative attitudes toward LGBTQ people in society. It sent a symbolic message that members of this group are second-class people with limited rights, and if injustice and violence are committed against them, they deserve it.

This influence can be seen in the shift in public opinion. Since 2013, the attitude toward LGBTQ people has become much more negative. In 2021, the Levada Center published the report “Attitude of Russians towards the LGBT community,” which clearly showed that Russians’ views of the LGBTQ community deteriorated after 2013. As of 2021, the most common attitude toward LGBTQ people in Russia was “disgust or fear” (38 percent in 2021, compared to 21 percent before 2013), while the proportion of those who were indifferent had declined by almost half compared to before the introduction of the law (26 percent in 2015 compared to 45 percent until 2013). Most people deny the right to engage in same-sex relationships (68 percent in 2021). This is an illustration of the hostile environment that has been created in part by the introduction of the “gay propaganda law.”

This change in sentiment has affected the level of violence against LGBT people. Our research shows that if in 2010 there were 46 hate crimes against LGBT people, in 2015 there were already three times more such cases (138). In general, the number of crimes increased substantially over the course of the decade (for more detail, see Figure 1).

Our data therefore demonstrate that discrimination does affect the level of violence perpetrated against members of the LGBTQ community. The “gay propaganda law” has increased the number of crimes committed against this social group. Gordon Allport, in his seminal work The Nature of Prejudice, called discriminatory legislation a mechanism that “deactivates the social brakes that prevent a hostile sentiment that exists in society from progressing into acts of violence.” Once these social brakes are removed, it launches an uncontrollable and unpredictable chain reaction in which random people around the country decide to attack LGBTQ people.

Conclusion

All the crimes that we identified after 2013 are, at least in part, the result of the existence of this law— the logical continuation of a state policy aimed at institutionalizing inequality against LGBT people. The German jurist and law professor Gustav Radbruch, analyzing the unjust laws of the Third Reich, developed the concept of “illegitimate law.” A law is considered such if the underlying legal concept “consciously disregards [the] equality of human beings”—“where justice is not even strived for, where equality, which is the core of justice, is renounced in the process of legislation, there a statute is not just ‘erroneous law,’ it is in fact not of a legal nature at all. That is because law, even positive law, cannot be defined otherwise than as a rule, that is precisely intended to serve justice.” Radbruch believed that illegitimate laws are dangerous because they create inequalities between different groups of people and put some of them in a vulnerable position. The “gay propaganda law” is an example of this. It imposes blanket restrictions on the rights of an entire social group.

A similar view on the law in question was provided by the European Court of Human Rights in Bayev and Others v Russia. The Court found that the law in question violated Articles 10 and 14 of the European Convention of Human Rights (ECHR), as it both infringed on freedom of expression and contravened the prohibition on discrimination. The Court specifically addressed the potentially dangerous societal effects of the law in question: “By adopting such laws, the authorities reinforce stigma and prejudice and encourage homophobia, which is incompatible with the notions of equality, pluralism, and tolerance inherent in a democratic society.”

Indeed, the existence of such legislation can be seen as part of the political regime. The development of anti-LGBTQ legislation took place at the same time as the formation of the authoritarian regime in Russia. In 2006, when the first regional laws restricting LGBTQ-related expressions were introduced, Russia was characterized as a hybrid regime by the Economist Democracy Index, even if some scholars claimed that Russia had already developed strong personalist autocratic rule. Seven years later, in 2013, when the “gay propaganda law” was expanded to the national level, the country was already classified as “authoritarian” by the Economist Democracy Index following Vladimir Putin’s return to the presidency in 2012, the subsequent consolidation of the regime, and the country’s turn to the rhetoric of “traditional values.” Finally, in 2022 Russia’s Democracy Index fell to its lowest level with the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, and interestingly enough, the “gay propaganda law” was once again a focus of the authorities: the scope of the law was expanded to cover the “promotion of non-traditional sexual relationships” to all citizens (not only minors, as it had been initially) and new bans were introduced on the “propaganda of pedophilia” and the “promotion of gender reassignment,” with the latter outlawing the change of legal gender. Therefore, the emergence and development of the “gay propaganda law” has occurred in parallel with the consolidation of authoritarian rule in Russia. Such legislation is employed by the regime for its own purposes. This law reinforces inequality against LGBTQ people and authorizes violence against the group.